The Parthians are basically considered in the historiography only as the Arsacid Parthians. But this view is both outdated and wrong. The Parthians outlasted the Arsacids and also the Sasanids, and therefore were even still present in post-Islamic Eran. This essay will show why confusion prevails regarding the exceedingly strong Parthian presence in Eran and what consequences this insight may have.

An Essay by Pīroz

The Parthians

The arrival of the Eranian Parni in the satrapy of Parthava and the successive establishment of the Parthian kingdom ushered in the Parthian era. The Parni, who settled in the new region and intermarried with the local Eranians, founded the Arsacid dynasty. The expansion from Parthava incorporated other satrapies and regions into the new Parthian Empire, which thereby came under the control of the Parthian Arsacids at this time.

The migration of the Parni into Parthava and their intermingling with local Eranians introduced the new type or identity as Parthians. Noble houses or feudal lords who took over the administration of territories or the command of armies in this empire entered history as Parthian figures.

The successful expansion of these players over areas such as Vergana, Media, Media Atropatene, Arachosia, and Aria led to either the early Parthianization of these areas or the incorporation of already Parthian territories. Since the Parthian arrival in these areas, a rapid establishment of the new rulers in these areas and cities can be observed. In particular, all of Media, Vergana, southeastern Eran, and the southern Caucasus show a strong Parthian presence very early on. It is striking that Median areas in particular are considered Parthian at an early date. This leads to the assumption that Median here takes the same role in relation to Parthian as Achaemenid does for Sasanian. Thus, Median lands or ethnies must have either been affine groups with the Parni-Parthavian Parthians, or they must have experienced early Parthian migrations that completely changed the demographic structure. In one way or another, these areas were completely Parthianized or significantly influenced by the Parthians. Later developments, different in strength but similar, occurred in Indo-Parthia, Mesopotamia, Armenia, and Caucasian areas such as Alwan (Arran) and Iberia.

Although Parthava, Vergana, Merw and central Media around Ragae and Spahan, were the main Parthian areas, a strong westward migration of the Parthians already took place very early. Ekbatana in Media became the summer residence of the Arsacids, Valaxshgerd (Ctesiphon) in Babylon the winter residence. Further, Arsacid families were installed in the Caucasus and Armenia, and Atropatene was taken over by Parthian governors. In the same era an immense exchange took place in Mesopotamia, where the Parthian presence and culture strongly asserted itself, to which still many events and finds, among other things in Hatra, testify.

West Migration and New Province

The westward migration of the Parthians is well documented. One of the most important events concerning this is the position of the province of the Parthians. In Achaemenid times, the extent of the province of Parthava (Middle Eranian: Pahlaw) could be described as follows (Ghodrat-Dizaji, 106): Vergana in the northwest, Khwarazm in the north, Sogdiana in the northeast, Balkh in the east, Herat in the southeast, and Kirman in the south. This extension was the case during the Achaemenids as well as during the beginnings of the Arsacids. However, the extent and location of the province probably changed at the earliest during the Arsacid expansion to the west, and certainly at the latest during the beginnings of the Sasanids. In the inscriptions of Shapur I (240-272 AD), no province called Parthava or Pahlaw is listed for the northeast anymore, but the province Abarshahr (“city/land of the Apar(ni)”) in approximately the same place. Later sources also no longer list a Pahlaw in the northeast, confirming that no province called Pahlaw existed in the northeast of the empire during the Partho-Sasanid confederation. This fact led some scholars to wrongly assume that the Parthians in the northeast of the empire suddenly disappeared from the scene because no one in the region spoke Parthian anymore or because the Arsacids were now defeated. But in fact, the fading of the Parthian language in his home region is due to two major, long-term events: One, the very early military colonization by the Parsigs, probably during the 4th and 5th centuries (Gyselen 2012, p. 156-157). Two, the later massive efforts of post-Islamic Iranian dynasties, such as the Samanids, to favor and extensively establish the Persian language as a language of administration and society. Thus, the Parthians in this region did not simply disappear, but were assimilated by the Parsigs. The developments hold political tendencies as well, considering that after the capture of this province, Shapur I changed the name to Abarshahr, built enormous military settlements with Parsig migrants, and had a new city, Nishapur, named after him, built around these settlements. It is true that the Arsacids had been defeated by the Sasanids and Parthav/Pahlaw was no longer mentioned in the northeast. But, first, the Parthians had still large control over parts of their native lands as later sources about the end of the last ancient Eranian empire show. Second, the Parthians and Pahlaw very well kept their place in the empire as a province, just in another location!

Shapur I now mentions Pahlaw along with Pars, Khuzistan, Meshan, etc. (Huyse 1999, 22-23). Kirder lists in the following order: Pars, Pahlaw, Asuristan, Meshan, etc. (Gignoux 1991, 61, 71). Ammianus Marcellinus (4 AD) mentions Parthia right after Pars and before Kirman (23.6.14, 357). The picture that hereby presents itself to us is a Pahlaw in the center of Eran, just north of Pars.

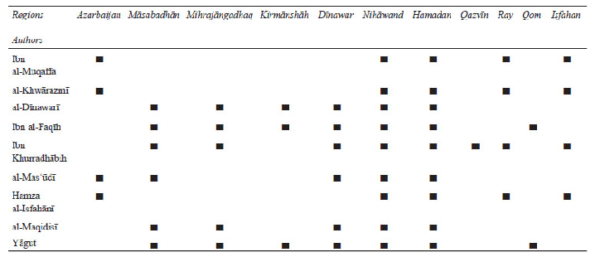

We get a more accurate, certainly more evolved picture of the province or region of Pahlaw from early, post-Islamic figures. At its greatest extent, Pahlaw at the end of the Partho-Sasanid confederation corresponds to Azerbaijan in the northwest (possibly with Tabriz and Ardabil as the northernmost border), Masabadhan (Ilam) and Mihrajangadhaq (Saymarah) in the southwest, Ispahan in the southeast, Ray and Qazvin as the northeastern border.

Fig. 1: Extent of Pahlaw (Pahla, Fahla) according to different Islamic authors. Ghodrat-Dizaji 2012: 109.

The localization of Parthia in the place where Media was before shows that until the end of the last ancient Eranian empire, the Parthians definitely inhabited this area. Migrations within the empire and successive naming of territories after their inhabitants were common in the history of the Eranian empires. For example, Sakastan, Abarshahr, Arabistan, etc. also received their names due to the demographic nature of the regions.

Fig. 2: Summarized extent of Pahlaw, mainly based on early Islamic authors, as also in respect of antique authors.

The position of Pahlaw and the Pahlawans in the center, north and west of the country is also confirmed by the reports about the traditional domains of the Parthian houses. These were mainly concentrated around Nahawand, Spahan, Ray, Adurpadegan, Abarshahr, Vergana and ancient Parthava, i.e. Eranian Khorasan including Merw and southern Turkmenistan (Livshits and Xurshudjan 1989, p. 170). Thus, there is no doubt that the region known as Pahlaw – along with core areas such as Abarshahr, Gorgan (Vergana), Parthav-Nisa (Mithradatkert), and Margiana – was fully or partially (in regard to Abarshahr, Parthav-Nisa, and Margiana) Parthian at the end of the Partho-Sasanid Empire and in the early stages of post-Islamic Eran. Parthian here not only as a term without meaning, but as the name of a locally present people with several dialects.

This fact is demonstrated, on the one hand, by the testimony of the Pahlaw region. But it is also supported by other indications:

- The existence of the collection of poems in local dialects known as Pahlaviyat or Fahlaviyat and which have a clear connection to northwestern Eranian languages. This name is based on the name given to these dialects, namely Pahlawi or Fahlawi, which means Parthian.

- Further, there are reports of the dialects spoken in these areas being called Pahlawi and Fahlawi respectively: “They spoke pure Pahlawi” for Zanjan (Encyclopaedia of Islam, p. 447, Volume 11) or “they […] spoke ‘Arabicised Pahlawi'” for Maraghe (Encyclopaedia of Islam, p. 498, Volume 6).

- Pre- and post-Islamic Parthian dynasties were present in these same areas, and social structures that supported the dynasties, political aspirations, and movements testify to idiosyncrasy and an inherent identity in this region.

The Confusion

The legitimate question arises, what has become of the Parthian people, when they had such a strong presence at the said time. The ignorance or lack of knowledge about the Parthian reality, which leads to the above question, is due to some factors and events. These have put a veil over the knowledge about this people that was once so powerful and had ruled the last Eranian empire with the Middle Persians:

- The Islamic foreign power introduced new terminologies and concepts, thus a new tradition. Their knowledge of Eran was mainly related to the Persian royal family, thus taking the Persian view of Eran as a standard. This was also fueled primarily by the dominance of the administrative Persian language. Only successively did Islamic historians and travelers realize that there were other peoples and that many regions that were often considered Farsi (Persian) had other ethnicities after all. But the damage had already been done. Although new evidence about these circumstances is available today, scholars have a hard time acknowledging the rough division of Eran into two parts at the beginning of Islamic expansion, namely the Pahlaw and Parsig factions.

- Included in this tradition was one of the greatest miss-happenings in history, namely the connotation of Pahlawi with Middle Persian. The development of the designation and meaning of Pahlawi certainly requires its own reappraisal. But it should be said here that Pahlawi did not refer to Middle Persian at the beginning of the Sasanid Empire. The Sasanid royal court was dominated by Parthian dynasts and generals in the early days, which forced the Sasanids to speak Parthian in the court (Gyselen 2012, p. 149-150). Thus, a Parthian court language commonly known as Pahlawi developed. This was basically nothing more than a continuation of the court language already in use during the Arsacids. The continued dominance of Middle Persian in the administration and management of the empire, however, led to the development of a Middle Persian heavily influenced by Parthian. This Middle Persian, which is also known to us from testimonies and inscriptions, was now called Pahlawi, following the language tradition at court. This was not because they wanted to refer to Middle Persian, but because they wanted to continue to refer to the (formerly Parthian) court language. The early Islamic historians, however, introduced with their historical elaborations – as so often – a wrong connotation and condemned Pahlawi – until modern times – with being the name for Middle Persian. In doing so, they removed Pahlawi from its proper domain, namely Parthian. This mishap led to historical confusion, if one now suddenly wanted to report about the Suren-Pahlaws, Mihran-Pahlaws, Karen-Pahlaws etc., who today are undoubtedly known as Parthians and who ruled the cities of Pahlaw like Ray, Nehawend, Spahan, Adurpadegan, or even Sakastan, Abarshahr, Merw etc. Or when talking about sources and their language, using “Pahlawi”, one now also had to puzzle whether it was Middle Persian or Parthian that was meant. But early historiography in the West for a long time remained in the dark about the true meaning of Pahlaw and Pahlawi, and despite the new findings, has not adapted to this day. This is a mistake that modern science is willing to make. Incidentally, the proper name of the Pahlavi dynasty, which actually wanted to refer to the Sasanids with “Pahlavi,” was also based on this historical mishap, and probably unintentionally called itself Parthian, in the true sense of the term.

- The stubborn insistence on the opinion that the Parthians were merely the Arsacids, and the ignorance about the domination of Parthian dynasties and houses over their traditional territories is another factor. Also factored into this point is the intentional adoption of foreign perspectives and thus decontextualization and fragmentation of Parthian history. For example, the Arsacids in Armenia are included in Armenian history, the Parthians in Iberia and Arran in Caucasian history, the Parthians in Sakastan and Hind in Persian or even Indian history, and the Parthians in Media and Abarshahr in Persian history. However, when a Parthian perspective is taken, we soon realize the magnitude of this injustice done by history and scholarship to the Parthians, and the heritage that has been stolen from them.

Thus, if the fragmenting perspectives are set aside and Parthian history is viewed from a Parthian perspective, as it deserves to be, then a new picture emerges that is capable of resolving many such confusions and unresolved questions in the history, anthropology, and ethnology of the Eranian cultural area. An achronological Parthian view of the region, without forgetting the historical developments, is able to create a Parthian overall picture, which may possibly help to gain new insights:

Fig. 3: Adding historical Parthian regions to each other, holistic view.

The picture shows the core regions of the Parthian people, without listing details such as the Parthian houses in their respective cities and regions (for example, also in the Caucasus) or Parthian influences in Mesopotamia, Anatolia and Central Asia. The map serves to understand the extent of the core Parthian history and to take a correspondingly correct view towards the Parthians as a people. Only in this way are we able to see the Parthian reality in its true form from the arrival of the Arsacids up to the events surrounding the last Parthian dynasts and Sufis until the 12th century, as well as the last Parthian remnants in literature, folk myths and northwestern Eranian culture.

List of References

Encyclopaedia of Islam. 1991. Volume 6 (edited by Bosworth, C.E., van Donzel, E., Lewis B., Pellat, Ch.), Leiden, E.J. Brill.

Encyclopaedia of Islam. 2002. Volume 11 (edited by Bearman, P.J., Bianquis, Th., Bosworth, C.E., van Donzel, E., Heinrichs, W.P.), Leiden, E.J. Brill.

Ghodrat-Dizaji, Mehrdad. 2012. Remarks on the Location of the Province of Parthia, in The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: Adaptation and Expansion (edited by Sarkhosh Curtis, Vesta, Pendleton, Elizabeth J., Alram, Michael, Daryaee, Touraj), British Institute of Persian Studies (BIPS), Oxbow books, Oxford & Philadelphia.

Gignoux, Philippe. 1991. Les quatre inscriptions du mage Kirdīr: textes et concordances, in Studia Iranica. Cahier 9, Union Académique Internationale : Association pour l’avancement des études iraniennes.

Gyselen, Rika. 2012. The Parthian Language in Early Sasanian Times, in The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: Adaptation and Expansion (edited by Sarkhosh Curtis, Vesta, Pendleton, Elizabeth J., Alram, Michael, Daryaee, Touraj), British Institute of Persian Studies (BIPS), Oxbow books, Oxford & Philadelphia.

Huyse, Philip. 1999. Die dreisprachige Inschrift šābuhrs I. an der Kaba-i Zardusť (šKZ), in Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, Pt. III, 2nd Vol, School of Oriental and African Studies.

Livshits V.A., Xurshudjan, E.S. 1989. Le titre mrtpty sur un sceau parthe et l’arménien mardpet, Studia Iranica 18.

Marcellinus, Ammianus. 1911. The Roman History of Ammianus Marcellinus (Translated by C. D. Yonge, M.A.), London, G. Bell and Sons, Ltd. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/28587/28587-h/28587-h.htm