The Parthians led their army according to Eranian and Mithraist tradition, which was more similar to the Sarmatians and other nomadic peoples in its mentality, military nature and combat tactics. In contrast to these nomadic organized collectives, however, the Parthians had gained imperial power.

A Narrative by Rayber

Edited and Enhanced by Deniz

Introduction

The Parthian army and military tradition differs itself significantly from the late Median and Achaemenid methods, as the latter was strongly Mesopotamian and had moved far away from the warlike ancient Eranian way of life. The Parthians on the other hand led their army according to Eranian and Mithraist tradition, which was more similar to the Sarmatians and other nomadic peoples in its mentality, military nature and combat tactics. In contrast to these nomadic organized collectives, however, the Parthians had gained imperial power. The combination of the resources of an empire and the preserved Erano-Aryan military tradition were sometimes the reason that the Parthians and the Parthian state could become a superpower at all. This extent is evident when one considers that only the Roman Empire was equal to the Parthian Empire and on the same level.

How powerful the Parthians and their armies were, appeared in the Battle of Charrae (Harran). The 36,000 Romans (28,000 infantry, 4,000 auxiliary soldiers, 4,000 horsemen) surrendered against 50,000 Parthians. Imperium Parthorum, as it was called by the Romans, was the strongest and most powerful enemy of the Rome. Long-standing wars between Rome and Parthia, which went down in history as the Roman-Parthian wars, are a series of conflicts between the two superpowers.

The Battle of Harran is one of the most famous, in which the Romans face one of their greatest defeats. Under the Eran-Spahbed Surena, the Parthians managed to defeat the Romans and carry out further offensives over the traditional border west of the Euphrates. 10,000 Roman soldiers from the Battle of Harran are taken into captivity and sent to Merv, the capital of the Parthian region of Margiana, for forced labor in the east of the empire, where the Parthians used the prisoners to build a mighty fortification ring around the whole city.

The Military Organization

As their nomadic pastoralist tradition shows us in multiple occasions; the Parthian people were excellent warriors. Thus, as a proper phenomenon; the main bulk of their armies consisted of cavalry forces. Although infantry troops too have been used in a lesser degree.

The Arsacid army had fixed garrisons at borders, consisting of ground troops. In the battles, however, the “Hamspah” (soldiers) gathered together from all over the empire under noble troop leaders, the “Azat”. An army, “Spah” or “Spad”, consisted of about 10,000 soldiers, from which it was divided into 10 sub-units of 1,000 men each, for “drafš”, these in turn into hundreds, “wašt” (Shahbazi 1986, p. 489-499). The “Spahbed” was the general, whereby the “Hazarbed” subordinated to him was responsible for 1,000 men. Likewise subordinate to the “Spahbed” was the “Argbed”, literally the Burgchef (Shahbazi 1986, p. 489-499; Shayegan 2003, p. 93-95).

It seems like (as the aforementioned paragraph may suggest) the general consensus is that Parthian Empire had no standing army. This interpretation finds its source in contemporary Greco-Roman historiography. Namely this passage from famous Greek historian Herodian of Syria is using as an argument:

„He [Pescennius Niger] also sent word to the king of the Parthians [Vologases V], to the king of the Armenians, and to the king of the Hatrenians, asking for aid. The Armenian king replied that he would not form an alliance with anyone, but was ready to defend his own lands if Severus should attack him now. The Parthian king, on the other hand, said that he would order his governors to collect troops – the customary practice whenever it was necessary to raise an army, as they have no standing army and do not hire mercenaries.” – Herodian [3.1.2]

Today all available histories about Parthian society and state came from the sources outside of the empire, mainly from the Greco-Roman world. That’s why we need to consider them with carefulness, they don’t have generally full scale information and the writers do not attempt to hide their despisal about their eastern neighbours. Though it is true that Parthian King of kings had no standing “royal” army in his possession, the system under the Arsacid rule was an effective military organization includes considerable numbers of professional troops.

The seemingly lack of central control in the administration effected the mainstream approach to the Parthian Empire. Many modern scholars with their ancient counterparts saw the empire as a loosely tied confederation of kingdoms non-independent only in name. These kingdoms were a constant threat to the empire’s unity and stability. In reality both kingdoms and Parthian King of kings profited their relationship. Kingdoms needed support against external threats (especially against the might of Rome) that they can not resist on their own, trade links and the recognition of their status. On the other hand Parthian King of kings needed their support in wars (Brosius 2006, p. 116-117). This is not a weakening ill system, but a very effective governance with a firm military arm.

First of all, we know there were full time soldiers at border forts and town garrisons (Hauser 2006, p. 310; Shahbazi 1986, p. 489-499). More importantly the main striking force of Parthian armies were higly professional heavy cavalry units. In his epitome of Pompeius Trogus’ Philippic Histories, Roman historian Justin wrongly emphasizes that among 50,000 cavalry faced Mark Anthony’s army in his 36 BC campaign, only 400 of them were free men (liberi), and the rest were slaves (servitori) (Justin, 41.2.5; 6). This is a misinterpretation of word “Azat”; the word literally means “free” (Chaumont, Toumanoff 1987, p. 169), but as we mentioned above it’s also used for nobility. Oddly, confusion of the writer increases even further; right after saying those horsemen were slaves he continues: “…Indeed the difference between slaves and freemen is, that slaves go on foot, but freemen only on horseback.” (41.3.4). We know from both Parthian and early Sasanian writings that (“ʾsbʾr” in Parthian, “asbārān” in Persian for cavalry) there were horsemen organized under their lords or magnates. These free men fully equipped by their masters with the land revenues in a feudal manner (Lukonin, 1983, p. 700). Therefore the rest of the army could easily be understood as their dependants, not as slaves (Lukonin, 1983, p. 700). With a proper consideration of historical data, we see large numbers of free professional soldiers ready to serve under their noble lords. As Hauser indicates: “The category of horse-riders (Greek: ἱππεῖς, Persian: asvārān) is, therefore, primarily a military and functional entity and not necessarily a social group.” (Hauser 2006, p. 304).

Consequently the Parthian King of kings had his ready professional army as well as levies through the subordinate kings and governors. He delivered the matters of military to his subordinates, and when needed effectively got his armies together. The Parthian army had both regular and irregular forces. So when one considers the issue in this perspective, as an attributed weakness of military power; the absence of a standing army actually doesn’t exist.

Units and Battle Tactics

The main component of Parthian armies were the horse-archers or light cavalry. Fundamentally as nomads, Parthian horse-archers had had great experience in steppe warfare. They had no armor, their clothing was reflecting other Iranian nomads; a belted tunic or kaftan like top, long trousers and boots (Brosius 2006, p. 120; Wilcox 2001, p. 12) (Fig 1). They used composite bow. This type of bow heavily used by the peoples of the steppe, it had more endurance and range than the self bow; it was reaching up to 150 meters still with good penetration (Ellerbrock 2021, p. 85). An iconic technique carried out by Parthian light cavalry was; while riding their horses turn and shoot backwards. Although it was not invented by the Parthians, made famous by them, and known in the West as the “Parthian shot” (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1: Parthian horse-archer relief plaque. He is drawing a composite bow, wearing trousers and belted tunic, he has a four-lobed dagger in his thigh and another sword. 1st – 3rd century AD. Museum Number: 135684, British Museum.

Fig. 2: Cylinder seal fragment. Horseman shoots a beast with “Parthian shot”, ca. 5th century BC. Museum Number: 89816, British Museum.

The heavy cavalry probably invented by Iranian Massagetae people from Central Asia around 8th century BC (Farrokh 2005, p. 3; Nicolle 1996, p. 9; Wilcox 2001, p. 9). Armored horsemen used by various other Iranian nomads (Schythians, Saka, Sarmatians, Alans) throughout ancient period. This type of heavy cavalry known in the West as “cataphract” (from Greek Κατάφρακτος: fully armored). Achaemenid Persians (though not as effective as Parthians and later Sassanians) had used heavy cavalry too; Xenophon describes Prince Cyrus’ heavy cavalry contingent (Xenophon, Anabasis, 1.8.6) yet their horses were not fully armored. The cataphracts used by Parthians, on the other hand was equivalent of tanks in their period. Horses wore scale armored blankets (Fig. 3) and chanfron, riders also had scale armor. Riders carried a lance, a longsword, a composite bow and also could carry a mace or a dagger (Fig. 4; 5)

Fig. 3: Horse armor from Dura Europos, ca. 165–256 AD. Yale University Art Gallery.

Fig. 4: Graffito of a charging cataphract from Dura Europos. Ellerbrock 2021, p. 86.

Fig. 5: Possible early Parthian clay plaque. A cataphract thrusts his spear into a lion. 3rd – 2nd century BC. Museum Number: 91908, British Museum.

A smaller portion of the Parthian army consisted of infantry. They were generally supportive in battles. There could be peasant levies and mercenaries (Brosius 2006, p. 122). In an infantry based warfare, Romans were clearly superior. So Parthians had never attempted to brought their infantry before well disciplined legionaries. Similarly their infantry could be no match against the nomadic hordes of the Central Asia (Shahbazi 1986, p. 489-499).

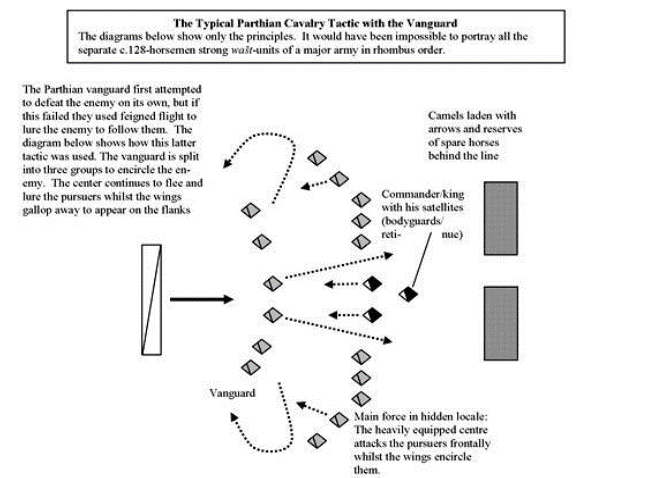

Parthians used an effective combination of heavy and light cavalry. Horse-archers’ role was harassing the enemy. The center had the heavy cavalry or cataphract forces. The wings consisted of light cavalry. Parthians favored the crescent formation (Syvänne 2017, p. 39); that the wings arrayed in a wide crescent-like shape. This was allowing the wing troops a better shooting angle and distributing more chaos into the enemy lines, and also creating a false corridor into the army’s center. They used that effect particularly in a double line formation (Fig. 6); which a vanguard attacks enemy lines, tries to crush them with their arrows. If this first attack cannot succeed, the center of the vanguard starts a feigned retreat while still shooting arrows, also wings keep harassing the enemy. Exhausted enemy pursues the vanguard right into the trap, that they meet with fresh heavy cavalry, at the same time both lines of horse-archers outflank the enemy (Syvänne 2017, p. 41) (Fig. 6). If there’s a single line formation, both heavy cavalry center and the wings would use simply hit and run tactics and try to break enemy lines (Syvänne 2017, p. 41) (Fig. 7). Parthian armies could resume these hit and run tactics for considerably long hours, until completely destroy the enemy’s morale or stamina. Main reason for this that they had huge numbers of reserves. Behind the battle lines they always kept spare horses and camels carrying weapons and arrows (Ellerbrock 2021, p. 87; Syvänne 2017, p. 39). So when horses exhausted riders could replace them with fresh ones, and when they used all of their arrows they could resupply themselves. They also had kettle drums that they beat continuously in order to create fright and unrest among enemies (Ellerbrock 2021, p. 87; Syvänne 2017, p. 42).

Fig. 6: Double line formation of Parthian army. Syvänne 2017, p. 41.

Fig. 7: Single line formation of Parthian army. Syvänne 2017, p. 42.

Conclusion

Although this higly mobile and creative tactics were fruitful against Romans in the open field, Parthians generally lacked of effective siege enginery. This was an important phenomenon that limits their offensive capability against Rome. Even if they would have siege engines, cavalry based armies wouldn’t have the same efficiency against a fortified town or a castle because of lack of good infantry. Without holding these, a big army couldn’t supply itself in the enemy territory for long periods. Also a prolonged siege would certainly give time to Roman troops to reorganize a counter-attack. With all of these factors considered, it was almost impossible for Parthian troops to long term occupation of Roman provinces. One can say the general power balance between Rome and Parthia called into being by their respective ways of warfare. Rome could penetrate into the Parthian territory, or even capture the capital; but it had never been able to fully destroy Parthian armies in the battlefield. Whenever Romans gained the upper hand in a battle, way more mobile Parthian armies could easily retreat from the field deep into their territory. Without fully crushing the military capability of Parthians, Romans always failed to subjugate the realm. On the other hand (as we discussed above) Parthians couldn’t complete their victories in the battlefield with conquering Roman provinces.

In short; Parthians have developed an effective military way to counter their eastern and western neighbours; this was especially important against higly disciplined infantry armies of the Rome. Their military prowess stopped the super-power of their era; the ever-conquering Rome, and lifted them to the imperial status. This created a balance between two super-powers for centuries. The Parthians’ strategic goal was to maintain this balance (few exceptions aside), and they were successful in doing so. Their downfall came from inside, not from the Romans or other neighbours. That can give us the idea, how powerful and efficient the Parthian miltary tradition.

List of References

Ancient Sources:

Herodian of Syria. History of the Roman Empire since the Death of Marcus Aurelius. Online English translation in: https://www.livius.org/sources/content/herodian-s-roman-history/

Justin. Epitome of Pompeius Trogus’ “Philippic Histories”. Online English translation in: http://www.attalus.org/info/justinus.html

Xenophon. Anabasis. Online English translation in: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3atext%3a1999.01.0202

Modern Sources:

Brosius, Maria. 2006. The Persians: An Introduction. Routledge, Abingdon & New York.

Chaumont, M.L., Toumanoff, C. 1987. “ĀZĀD (Iranian Nobility)”, in Encyclopedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 2, pp. 169-170.

Ellerbrock, Uwe. 2021. The Parthians: The Forgotten Empire. Routledge, Abingdon & New York.

Farrokh, Kaveh. 2005. Sassanian Elite Cavalry: AD 224-642. Osprey Publishing, New York & Oxford.

Hauser, Stefan R. 2006. “Was There No Paid Standing Army? A Fresh Look on Military and Political Institutions in the Arsacid Empire”, in Arms and Armour as Indicators of Cultural Transfer. The Steppes and the Ancient World from Hellenistic Times to the Early Middle Ages (Nomaden und Sesshafte 4), (edited by Mode, Markus, Tubach, Jürgen), Reichert, Wiesbaden, pp. 295-320.

Lukonin, V.G. 1983. “Political, Social and Administrative Institutions, Taxes and Trade”, in Cambridge History of Iran III/2, Cambridge University Press, Cambrigde, pp. 681-746.

Nicolle, David. 1996. Sassanian Armies: The Iranian Empire early 3rd to mid-7th centuries AD. Montvert Publications, Stockport.

Shahbazi, A. Sh. 1986. “ARMY i. Pre-Islamic Iran”, in Encyclopedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 5, pp. 489-499.

Shayegan, M. Rahim. 2003. “HAZĀRBED” , in Encyclopedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 1, pp. 93-95.

Syvänne, Ilkka. 2017. “Parthian Cataphract vs. the Roman Army 53 BC-AD 224”, in Historia I Świat 6, pp. 33-54.

Wilcox, Peter. 2001. Rome’s Enemies (3): Parthians & Sassanid Persians. Osprey Publishing, Oxford.