By Varan Alan

This work provides a comprehensive compilation of current research by renowned scholars focused on the Zaza language (Zazaki). Central to the discussion is the analysis of the linguistic roots and origins of Zazaki, particularly within the context of Iranian languages, more specifically within the Parthian environment. This analysis is supported by historical studies, with narrative elements added to bring structure to life.

The findings suggest that Zazaki does not share a closer kinship with Persian or Pashto within the Iranian-Aryan language family. Instead, it appears more closely related to the written form of Manichaean Parthian. Importantly, although Zazaki and the ancient written Manichaean-Parthian do not share a direct lineage, no other Middle Iranian language has been identified as more closely related to Zazaki. Both written Manichaean-Parthian and Arsacid-Parthian are recognized as its closest known relatives. Modern Persian and Pashto, on the other hand, are significantly more distant linguistically, with their predecessors being even further removed from Zazaki.

The Iranian languages, a subgroup of the Indo-European family, are known for their diversity and historical depth. Within this group, however, two languages stand out for their striking similarity: Zazaki and Arsacid-Parthian. The following analysis explores the unique connections between these two languages, setting them apart from other Iranian languages. These connections, ranging from shared linguistic features to a common vocabulary and similar grammatical structures, provide valuable insights into the development of Iranian languages.

1. Professor Jost Gippert Zur Dialektalen Stellung des Zazaki

Zazaki as a “Parthoid” Language

Professor Jost Gippert suggests that Zazaki, Gōrānī, and Semnānī are closely related Northwestern Iranian languages, a connection supported by shared archaic traits in phonology and morphology. He argues that a closer relationship between Zazaki and Persian cannot be established as it can with Arsacid-Parthian. The shared archaic features in Zazaki, Gōrānī, and Semnānī indicate that these languages, along with the written forms of Arsacid and Manichaean-Parthian, are indeed closely related.

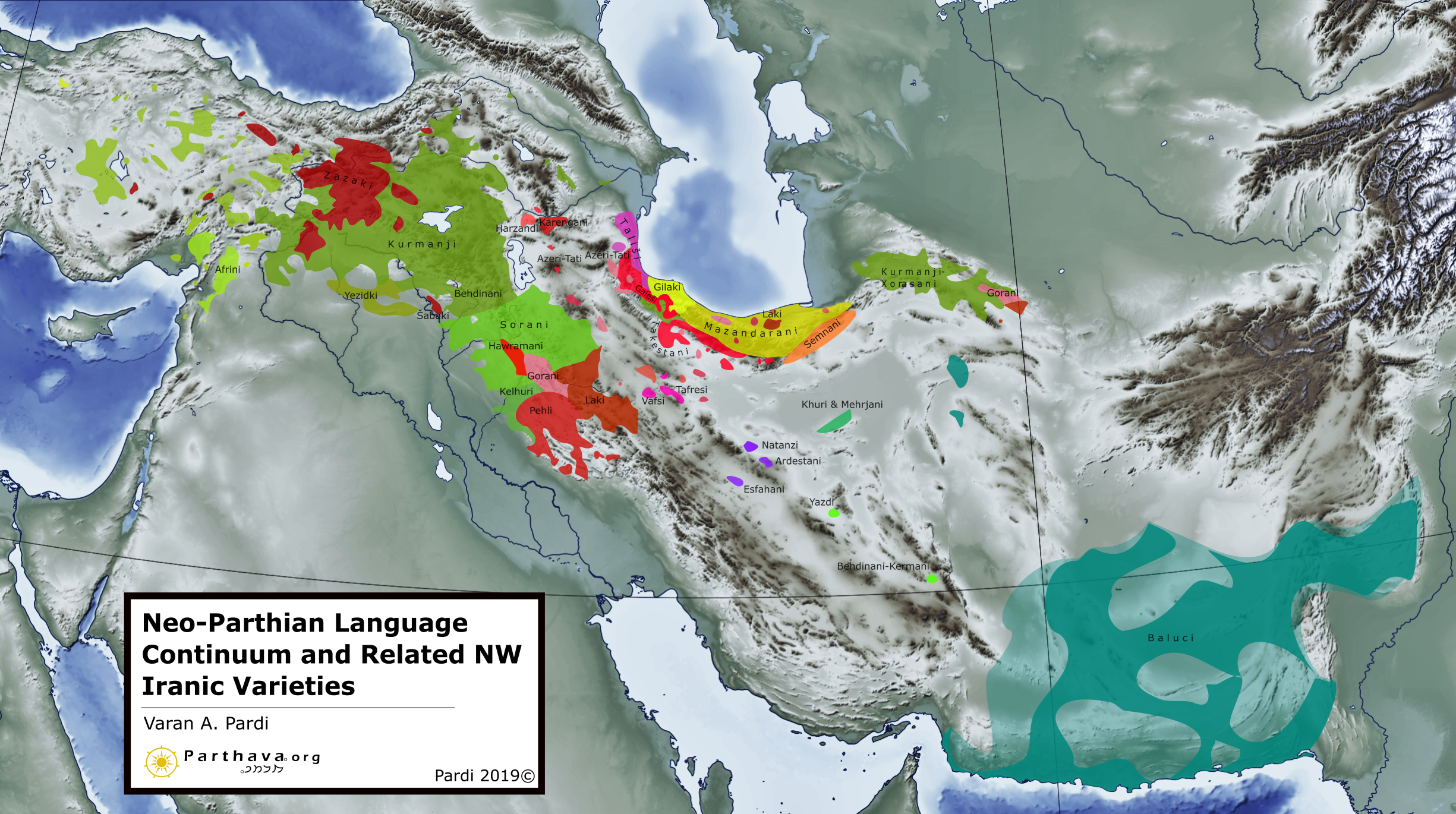

Parthian, particularly in its Manichaean form, exists only as a written language and is viewed as a near relative of this language group. However, it shows specific innovations, such as the elimination of gender differentiation, not adopted by the so-called “Parthoid” languages. Professor Jost Gippert labels these languages—Zazaki, Gōrānī, and Semnānī—as “Parthoid.” These languages exhibit strong Parthian influence and were historically known as Pahlawani (Parthian) dialects within the Iranian world. Gippert addresses the misconception of drawing a rigid boundary between Parthian and non-Parthian languages based solely on the written Arsacid-Parthian records.

The Parthians spread westward from the Euphrates and the Caucasus to Northwest India and Central Asia. This vast expanse included various Parthian noble houses divided into multiple clans, resulting in diverse Parthian dialects and substrates. It should be noted that Arsacid existed only as a written language and was used administratively at least 1500 years ago, whereas Zazaki is a Neo-Iranian language. The intermediate stages in the development of the Parthian complex would further clarify this progression.

More detailed historical explanations are provided in the book Parthavname (2023).

Linguistic Analysis by Professor Jost Gippert

- Verbal Isoglosses: In Zazaki and Imperial Parthian (Court Parthian/Arsacid), causative forms with an -n- suffix appear, which do not exist in other Iranian languages. For instance, the verb “to burn” appears in Zazaki as “daz-n-” (PP dazna) in the transitive form and “dez-” (PP deza) in the intransitive form. Parthian has similar stems, such as wygrʼn- (wiγrān-, “to awaken”) vs. wygrs- (wiγrās-), PP wygrʼd (wiγrād, “to wake up”).

- Passive Forms: Zazaki has distinct passive forms with an i- suffix, similar to Imperial Parthian, although the latter more frequently uses an -s- suffix. For example, the verb “to tear” is represented as “bır-i-” (PP bıria) in the intransitive form and “bır̄-n-” (PP bır̄na) in the transitive form.

- Lexical Matches: There are vocabulary similarities between Zazaki and Parthian. For example, Zazaki vaz- (PP vat), meaning “to say,” corresponds to Imperial Parthian wʼc- (wāž-, PP wʼxt- wāxt) “to say,” whereas in Persian, the word is gōy- (PP guft).

- Phonological Traits: Zazaki shares phonological characteristics with Imperial Parthian, despite some differences. Zazaki includes a tripartite opposition of stops, with a voiceless-glottalized series also found in Manichaean and Arsacid Parthian.

- Geographical Proximity: The Zazaki-speaking area lies along the western border of the ancient Parthian Empire, supporting the idea of continuous settlement by Northwestern Iranian (or Parthian) tribes.

- Differences with Persian: Zazaki exhibits unique features not found in Persian. For instance, the word for “to cry” in Zazaki is “berv-” (PP berva), corresponding to Imperial Parthian barm- (PP barmād), whereas in Persian, it appears as giry- (PP girīst).

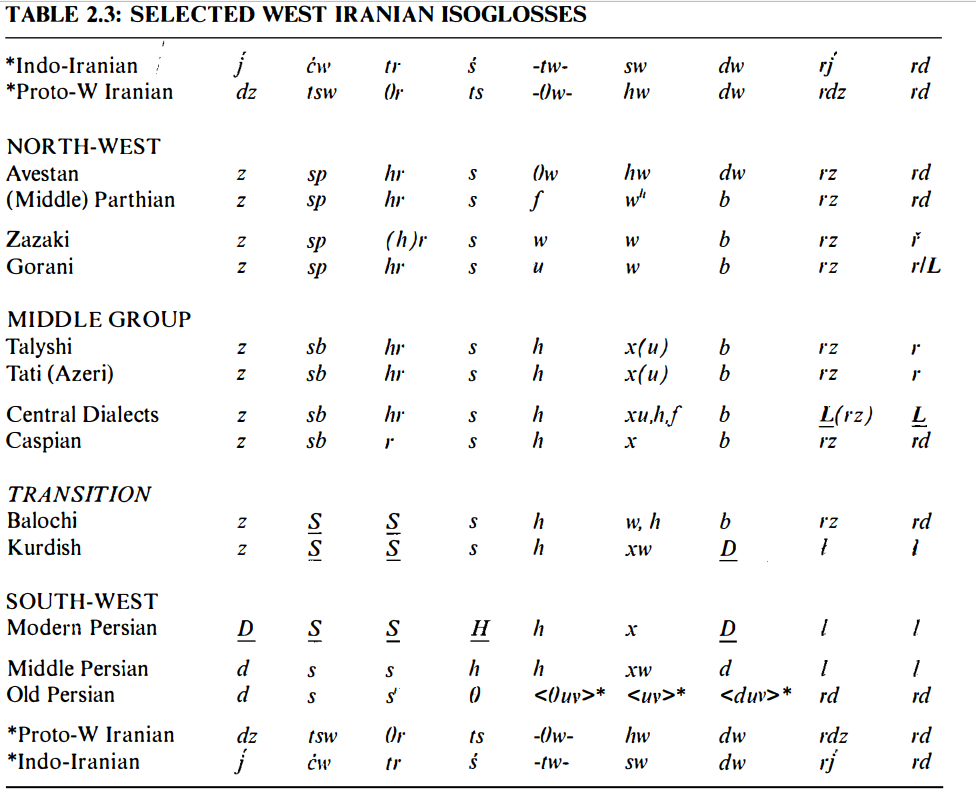

- Isoglosses: Isoglosses denote geographical or temporal boundaries indicating variations in linguistic features. Various isoglosses for modern Iranian dialects, including Zazaki and Arsacid-Parthian, are presented on page 2 of Zur dialektalen Stellung des Zazaki by Professor Jost Gippert. These isoglosses show distinctions in phonetic development between these languages and others, including Persian.

- Representation of Proto-Indo-European Palatals: In Persian, these are represented as h/d, while in Zazaki and written Arsacid-Parthian, they are represented as s/z. This phonetic distinction highlights a division between the Pehlewani/Parthian (Zazaki & Imperial Parthian-Arsacid) on one side and Neo-Persian on the other.

- Continuation of the Proto-Indo-European consonant clusters tr/tl: In Persian, this cluster appears as s, while in Zazaki and Arsacid-Parthian, it appears as hr, indicating another phonetic distinction between the larger Parthian and Persian groups.

These isoglosses suggest that Zazaki and Imperial Parthian are more closely related in phonetic characteristics than to Persian, supporting the idea of a closer relationship between Zazaki and Imperial Parthian than with Persian.

2. The Iranian Languages, edited by Gernot Windfuhr – Routledge Language Family Series

Here, too, a remarkable closeness to Arsacid-Parthian can be observed. What follows is a concise summary of an extensive work:

The relationship between Zazaki and Arsacid-Parthian is significant because they share several linguistic features that set them apart from other Iranian languages. Zazaki and Arsacid-Parthian exhibit similar phonetic characteristics, including the phonemes /z/ and /sp/, which contrast with other Iranian languages, such as Neo-Persian, which uses /D/ and /S/ instead.

In terms of morphology, Zazaki is considered the least innovative compared to Arsacid-Parthian, indicating a strong morphological connection between the two. Additionally, there are similarities in syntax: Zazaki, Gorani, and Central Plateau dialects most closely resemble Arsacid-Parthian in word order, as evidenced by the arrangement of N-EZ and AOJ.

The abbreviations N-EZ and AOJ refer to specific syntactic structures in languages. N stands for noun, EZ for Ezafe (a grammatical element in some Iranian languages that indicates a relationship between words, similar to genitive or adjective-noun relationships in German), and AOJ for adjective-object juncture. The statement that Zazaki, Gorani, and Central Plateau dialects resemble Arsacid-Parthian in their word order means that they share similar patterns in the arrangement of nouns, Ezafe, and adjective-object connections.

Geographical and historical factors also play a role in this relationship. Zazaki is a Northwestern Iranian language, more closely related to Gorani and Iranian Azari dialects than to Kurdish. This geographical proximity may have facilitated the exchange of linguistic features between Zazaki and Arsacid-Parthian. Overall, the close relationship between Zazaki and Arsacid-Parthian is evident in their shared phonetic, morphological, and syntactic characteristics, as well as their geographical and historical connections.

Regarding Kurdish

The relationship between Kurdish and Arsacid-Parthian is also noteworthy and is reflected in several linguistic similarities. According to studies by MacKenzie and Windfuhr, Kurdish is phonetically and morphologically close to Persian, which suggests a longer period of contact between these languages. This connection points to historical and geographical factors influencing the development of these languages.

Kurdish occupies an intermediate position between Northwestern and Southwestern Iranian dialects. Within Kurdish, the three main groups—Northern Kurdish, Central Kurdish, and Southern Kurdish—are quite distinct from each other, with Northern Kurdish, in particular, being mutually unintelligible with the other groups. In summary, Kurdish and Arsacid-Parthian share some linguistic commonalities. These similarities, combined with geographical proximity and historical contacts, suggest the possibility that Kurdish may have originated from the Parthian environment.

Regarding Taleshi, Gilaki, Mazandarani, and Semnani

The connections between the languages Taleshi, Gilaki, Mazandarani, Semnani, and Arsacid-Parthian are also significant and manifest in a variety of linguistic similarities.

As part of the same subgroup within the Iranian language family, Taleshi, Gilaki, Mazandarani, and Semnani are geographically and historically closely linked to Arsacid-Parthian. Their word structure is similar to Arsacid-Parthian, as evidenced by comparable patterns in the arrangement of nouns, Ezafe, and adjective-object connections (pages 104-105).

Gilaki and Mazandarani, spoken in the Caspian region, particularly show an affinity with Zazaki, indicating a former geographical closeness and potentially a common origin (page 105). Semnani, spoken in the Semnan region, also reveals a closeness to Arsacid-Parthian. It is suspected that Semnani and other regional languages may have originated from Parthian, supported by their similar phonetic and morphological characteristics (page 89).

These languages thus demonstrate a significant closeness to Arsacid-Parthian, reflected in their phonetic, morphological, and syntactic characteristics, as well as in their geographical and historical connections. This closeness is particularly notable compared to other Iranian languages, suggesting that they may have emerged from the Parthian context.

Zazaki among other Parthoid languages and other non-Parthoid NW Iranic languages

3. Professor Ludwig Paul The Position of Zazaki among West Iranian Languages

Shared Linguistic Features: The document states that “Zazaki and written (Arsacid-)Parthian share a number of linguistic features not found in other Iranian languages” (p. 12). This suggests unique similarities between these two languages that distinguish them from others within the Iranian family.

Shared Vocabulary: The document also mentions that “Zazaki has a substantial amount of shared vocabulary with (Arsacid-)Parthian” (p. 15), implying that the two languages share a considerable number of words, which may indicate historical contact or common origins.

Similar Grammar Structures: On page 18, the document notes that “Zazaki and (Arsacid-)Parthian have similar grammatical structures,” implying that the syntax and sentence structure of these two languages are alike, indicating a distinctly close relationship.

Zazaki, Gorani and Hawramani – Parthian (Pahlawani) Dialects?

Quote from Professor Windfuhr in The Iranian Languages, edited by Gernot Windfuhr:

“Zazaki and Gorani are the least innovative in relation to Parthian.”

This statement from Professor Windfuhr’s work highlights that Zazaki and Gorani retain linguistic features most similar to Parthian, displaying minimal innovation compared to other Iranian languages. This characteristic places them as the closest living languages to the ancient written Arsacid-Parthian. Their conservative nature preserves linguistic traits that bridge the gap between the Parthian language of antiquity and contemporary dialects, emphasizing their unique position within the Iranian language continuum.

This observation not only reinforces Zazaki and Gorani’s classification as “Parthoid” languages but also underscores their value in linguistic studies as living connections to the Arsacid-Parthian heritage. The fact that these languages are less affected by the shifts towards Middle Persian-type changes solidifies their role as critical sources for understanding the linguistic landscape of the Parthian period.

Parthian; Zazaki, Gorani, Gilaki, Talyshi, Semnani, Mazandarani – The relationship between Zazaki and written (middle)Arsacid-Parthian is clearly visible, followed by connections to Talyshi, Galeshi, Semnani, Gilaki, Mazandarani, and others. Baluchi and Kurdish serve as transitional languages within this continuum towards Persian (Source: The Iranian Languages, edited by Gernot Windfuhr)

Professor Gernot Windfuhr Quote:

“Overall then, from Zazaki and Gorani downward to Persian, the dialects are successively less ‘archaic,’ each subgroup accumulating additional innovations. At the same time, Persian has been increasingly the superstrate language, and as such may have most directly affected dialect groups in contact with it at various historical periods. This was probably the case with the ‘transitional’ Northwestern pair, Balochi and Kurdish, which have the Southwestern features tsw and Or > s, Ow > h. Kurdish, in addition, also shares dw > d and hw > XlV with Persian (where later XlV- > x-). As convincingly argued by Korn (2003), the two must have acquired those features when in contact with Persian for a considerable period of time, longer for Kurdish because of the additional two features (for such contact cf. also MacKenzie 1961 and Windfuhr 1975).”

The Misconnection with Middle Persian

When most people hear the term “Pahlavi,” many associate it primarily with Persian or Middle Persian, partly due to the legacy of the former Shah. In both cases, “Persia” or “Persian” comes to mind. However, it was originally the self-designation of the Parthians in its later Middle Iranian form.

The term “Pahlavi” or “Pahlawi” is still used in linguistics today with varying meanings. It refers both to Middle Persian, which was originally called Pārsīg, and to Middle Iranian, yet it also recalls ancient Parthian roots in the form of Pahlawani. The later use of “Pahlavi” by historians to refer to Middle Persian (Sasanian Persian) has caused confusion in academic circles, as Pahla originally denoted “Parthian.” This misunderstanding stems from the fact that during the Sasanian period until the 5th century CE, Parthian, or Pahlawi, was spoken at court, which led to the language of the Sasanian kings being known as Pahlawi. With this tradition changing as Middle Persian replaced Parthian, the misconception arose in the Middle Ages that Sasanian Persian was “Pahlawi.”

Today in Iran, the term parsi-ye miyane (Middle Persian) is predominantly used for Sasanian Persian, while Pahlawi and Pahlawani are used to refer to Parthian. The Kurdish and Danish scholar Mehrdad Izady argues that the works of Zakariya al-Qazwini were not translated into Western languages. In his work Al-Mu‘jam, he discusses the existing dialects of Pahlawani, which would include the groups Awrami, Gurani, and Dimili (Izady 2004: 205). The regions of these languages encompass the area of Fahla as well as the Arsacid-Armenian region.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study of Zazaki and related Northwestern Iranian languages such as Gorani and Hawramani reveals an intricate linguistic, historical, and cultural relationship with the Parthian (Pahlawani) heritage. These languages, now identified as “Parthoid,” exhibit distinct phonetic, morphological, and syntactic features that closely align them with the Parthian linguistic tradition, even if they are not direct descendants of the written Arsacid-Parthian. The 1500-year gap between the Arsacid era and the emergence of these Neo-Parthoid languages underscores the significance of intermediate linguistic and cultural evolutions that preserved and transformed the Parthian legacy.

The term Pahlavi has added complexity to this historical-linguistic puzzle. Historically, Pahlavi was rooted in the Parthian self-designation and was once associated with Parthian dialects. However, during the Sasanian period, this term was later misattributed to Middle Persian, leading to longstanding confusion. Only in more recent linguistic discourse has Pahlawi been recognized for its original association with Parthian dialects rather than Middle Persian. The works of scholars such as Mehrdad Izady emphasize that Zakariya al-Qazwini described dialects of Pahlawani—including Awrami, Gurani, and Dimili—as distinct linguistic entities, preserved in regions historically connected to the Parthian sphere, such as Fahla and the Arsacid-Armenian regions.

Moreover, historical narratives, literature, and cultural texts complement linguistic analysis by providing critical insights into the continuity of these languages within the Parthian legacy. The identification of Zazaki, Gorani, and Hawramani as “Pahlawani” or “Parthian” dialects in later periods attests to their historical significance and cultural continuity. This connection highlights how these languages were recognized within the Parthian sphere, not only by linguistic traits but by their deep integration into the regions historically shaped by Parthian influence.

Thus, the relationship between ancient Parthian and Neo-Parthoid languages such as Zazaki is a testament to the enduring influence of Parthian heritage. This heritage evolved through centuries of linguistic adaptation, enriched by historical narratives and literary traditions that provide a living link to the Parthian past and reveal the complexity of Iranian linguistic history.

List of References

Gippert Jost. 2008. Zur Dialektalen Stellung des Zazaki

Ludwig Paul. 1998. The Position of Zazaki among West Iranian Languages

Windfuhr Gernot. 2009. Routledge Language Family Series, The Iranian Languages

Mehrdad R. Izady. 2004. in: Ferdinand Hennerbichler: Die Kurden

Pardi A. Varan. 2023. Parthavname – Das parthisch-mithraistische Narrativ, Druck und Distribution durch epubli